TRAPPIST-1e: A Glimmer of Hope in the Search for Life Beyond Earth

Astronomers are cautiously optimistic about a tantalizing discovery: one of the planets orbiting the TRAPPIST-1 star system—located just 40 light-years from Earth—may possess an atmosphere capable of supporting life. But confirmation will require 15 more observations using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

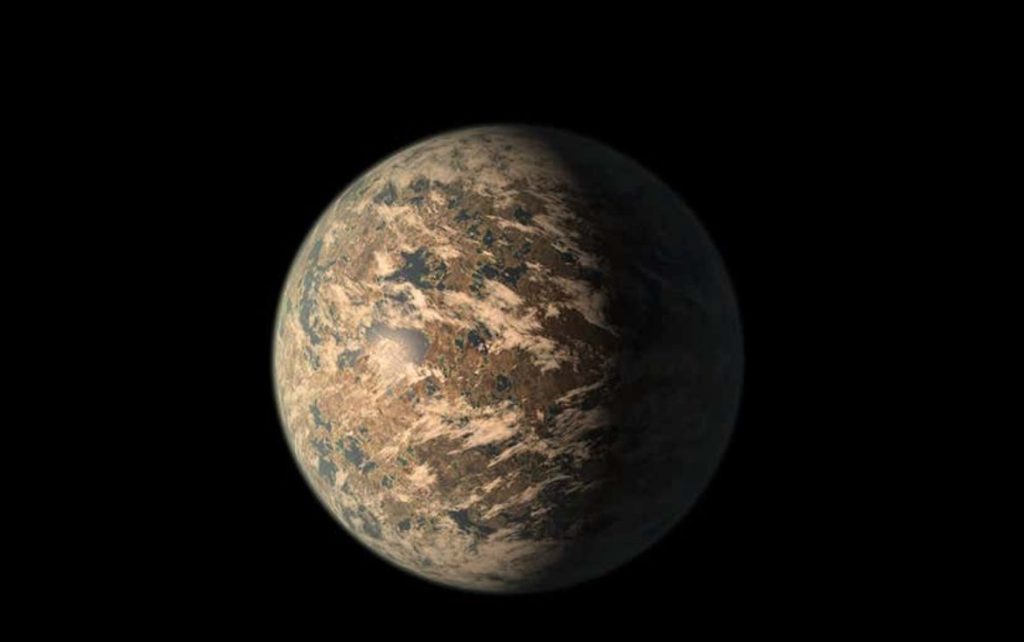

TRAPPIST-1, a small red dwarf star discovered in 2016, quickly captured the attention of scientists due to its seven Earth-sized planets, three of which lie in the so-called “Goldilocks zone”—the orbital sweet spot where liquid water could exist. Among these, TRAPPIST-1e stands out as the most promising candidate.

A Closer Look at TRAPPIST-1e

Ryan MacDonald, an astronomer at the University of St Andrews, and his team have been focused on TRAPPIST-1e for years. In 2023, they used JWST to observe the planet as it transited its host star. By analyzing how starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere, they can detect chemical signatures that hint at habitability.

However, TRAPPIST-1’s cooler temperature complicates the analysis. Molecules like water and methane—potential indicators of life—can also exist in the star itself, making it difficult to distinguish between stellar and planetary signals. To overcome this, MacDonald’s team developed new atmospheric models to isolate the planet’s spectral fingerprints.

Their preliminary findings suggest TRAPPIST-1e may have a nitrogen-rich atmosphere, possibly containing methane—an exciting prospect for astrobiology. “Of all the spectra we’ve obtained so far from the TRAPPIST-1 system,” MacDonald says, “this is the most promising.”

What Comes Next?

If further data confirms the presence of a nitrogen-rich atmosphere, scientists will begin searching for other gases like carbon dioxide and methane. These could help determine surface temperature and the potential for liquid water—key ingredients for life.

Still, caution prevails. With only four JWST observations completed, researchers stress that TRAPPIST-1e could still be a barren rock. “We need to shrink the error bars,” MacDonald notes. The team plans 15 additional scans to refine their models and conclusions.

The Bigger Picture

Matthew Genge of Imperial College London underscores the complexity of planetary habitability. “You can be the right distance from the star,” he says, “but with the wrong atmosphere, you end up with a Venus-like inferno or a frozen Mars.”

He adds that the presence of oxygen in an atmosphere would be especially compelling, as it likely requires photosynthesis—suggesting biological processes. “Sooner or later,” Genge predicts, “we’ll find a planet with a nitrogen/oxygen-rich atmosphere.”

And if TRAPPIST-1e is habitable? Genge muses on the implications: “Just imagine what’s gone on on that planet for the last 7.6 billion years. The older the planet, the more likely intelligence could evolve.”

Looking Ahead

MacDonald believes that by 2060, we may identify several planets whose atmospheric data defies explanation without invoking life. But he tempers expectations: “We’re a skeptical bunch,” he says. The road to proving extraterrestrial life is long—but TRAPPIST-1e might just be a step closer.